From Existentialist to Let's go Exploring - My Philosophical Evolution Since Age 20

- Tim Burns

- Apr 3, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 10, 2022

I’ve been an amateur philosopher for all my life. I’ve dabbled in Atheistic Existentialism, and Zen Buddhism, and now I’m trying to figure out where to go next.

During college, a roommate introduced me to the book Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre. The book saved my life. Each chapter was a gift that allowed me to deconstruct the toxic influences that made me unhappy.

I identified deeply with Roquentin, the protagonist of the story, who systematically deconstructs his delusions: family, work, love, religion, and knowledge. Gradually, he realizes that he, alone, determines his identity and his worth comes from within, not from the labels or responsibilities that others expect of him.

Before I was 20, the most toxic presence in my life at the time was my family and friends. When I decided to define myself outside of their expectations, it felt like coming out of a dank cell and into a bustling market, filled with freedom and opportunity. All the weight and constraints of having to be who others wanted me to be, or who they thought I was, all fell away. I felt like Marsinah in Kismet, skipping through the market and transforming into the person I wanted to be.

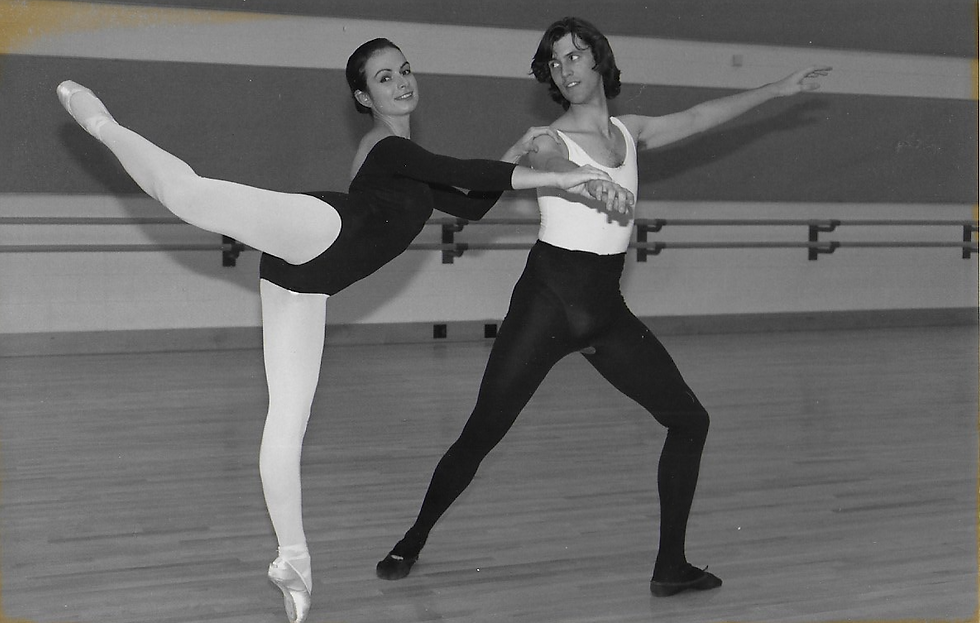

Photo by Ludovic Milin

After embracing the ideas of atheist existentialism, I understood that the expectations of others didn’t matter. The only thing that did matter is that I chose my actions that would lead to the consequences that I wanted for myself.

During the team I was reading and rereading Nausea, I was continually asked the question, “What is your major?” At that time, I had an official answer, “Mathematics.” It was sufficiently rigorous a study to shut down their perennial judgment, but I wasn’t going to get on board with any nonsense of having to justify myself by projecting a useful role in society that I would assume once the college money ran out. “Oh, so you want to be a teacher” was the smug response from my academic parents. My response was, “No. I want to be a professional ballet dancer.” Because that’s why I was studying Mathematics. It had the least number of core requirements of any major and I was able to justify my tuition while at the same time doing what I really wanted to do, which was dance.

Eventually, the college money did run out. My father died suddenly and I was released from his destructive tirades. I took the life insurance money, bought myself a car, and drove from Fort Collins, Colorado to a new life in Salt Lake City, Utah. It was far enough away to buffer me from the latent vindictiveness of a dysfunctional family, but not far enough to be completely estranged.

At that time, I knew a few things:

I was an atheist existentialist and I would define myself — not my friends, my family, or my lovers

I loved ballet and had gotten passably decent at it

Taking the hardest math classes with a C/B average had given me the ability to concentrate on really boring topics

I could use the bits and pieces of computer knowledge I picked up during my teenage years to make money

Photo by Ludovic Milin

I took those truths and wheedled my way into a job at the University of Utah Center for High-Performance Computing. It was the break I needed. I realized that I needed to bring my C average up in order to graduate, so I enrolled in every math class I could. One of those classes was taught by a professor named Bob Palais. He became a friend and a mentor. He also was probably the first professor to recognize that I wasn’t just a loser and said I had the best intuitive understanding of the Chaos Theory of any student he had ever had. By this time, my mathematics was advanced and we were doing Chaos and Dynamic systems, modeling complex physical processes, and optimization problems. I had found my calling in front of a computer and I was making enough money ($25K per year) to pay the rent and eat.

Bob also was a Buddhist. He and I were talking one night and I discussed existentialism. He was the first person since Boudjema that had read Satre and understood it well. In such a quiet and Zen way, he explained how the isolationist individual of Sartre’s existentialism left him empty and how connections were the key to understanding the meaning of human existence. I had a deep respect for him and the words sunk in and I began to ponder them.

That notion of connectedness stuck with me and I started attending 6 am chanting and meditation sessions at the Providence Zen center while my mom was dying. It was a time when I needed grounding and ultimately, the Korean chanting and Buddhist religion were too foreign to my western mind to stick, but I believe still in the fundamental truths of the Koans and the power of meditation.

We are not defined by others, but we are all connected. I can do good for all by doing good for one. I don’t need to make things happen as much as I need to understand how my thoughts and deeds fit into everything that is happening.

Since 2014, I have been a member of a Unitarian congregation at the First Unitarian Church of Providence. The Judeo-Christian spirituality doesn’t speak to me in the way that Zen meditation did, but the connectedness is stronger. As a westerner, I understand the foundations of the Unitarian religion far better than Zen.

I feel I’m at a crossroads now where I need to find out where I am going with my spirituality and start the next step of my journey.

Maybe all the Spirituality I needed was in Calvin and Hobbes

Comments